Reflected DLL Injection

In my last post, I explained what was a DLL and how attackers can inject malicious Dlls in the context of other processes and make them execute the malicious code. However, a basic DLL injection is easily detectable by security tools such as Crowdstrike.

A Reflected Dll Injection is another technique that wants to achieve the same goal, but the DLL doesn’t need to reside in disk. Remember that when performing a normal DLL injection, we had to write the path of the DLL in the other process memory and then make a new thread execute the LoadLibrary function with that path as an argument. This implies that the malicious DLL has to reside somewhere in the disk (hence, it can be easily detectable).

If now the malicious DLL doesn’t exist in disk, the LoadLibrary function can’t be used since it requires a path to load the DLL. That’s why in a Reflective DLL attack, he attacker has to create its own “ReflectiveLoader” function.

Before delving into details about the Reflective injection, let’s first clarify two concepts related with virtual memory that are important.

VA and RVA

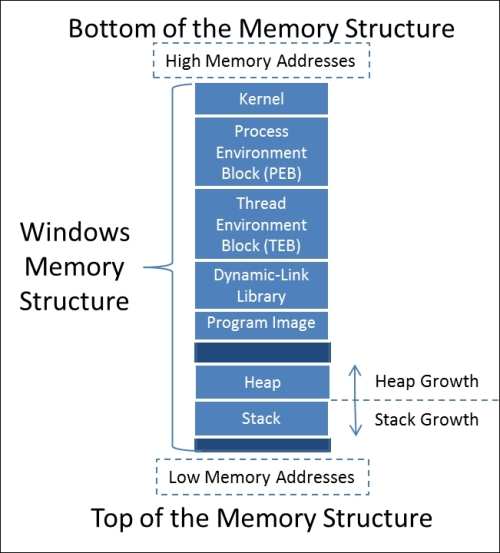

VA stands from Virtual Address and RVA is the Relative Virtual Address. applications on’t access physical memory, they only reference virtual addresses from the virtual memory. Virtualizing access to memory provides flexibility in the way applications use available physical memory. An application may be splitted in different blocks in the physical memory.

The Relative Virtual Address is not an absolute address, but an offset from the base virtual address of a module. Instead of relying on a fixed address, the code can use an RVA to refer to memory locations relative to the module’s start.

Imagine you have a module loaded at virtual address 0x10000000. If within that module, there is a resource located at 0x10000100, its RVA would be 0x100 (because it is an offset of 0x100 from the module’s start).

Reallocation Table

Another important topic to mention is the Reallocation Table. When a program is compiled, the compiler has to assume that the program will be loaded at a certain base address. This address will probably change each time the PE is loaded, but since the compiler doesn’t know this, it assumes one. This base address is saved atIMAGE_OPTIONAL_HEADER.ImageBase in the PE headers.

Since the compiler may hardcode some addresses within the executable, if the base address changes, then these hardcoded addresses will be incorrect and fail.

To avoid this, the compiler add all the hardcoded directions in a data directory named .reloc , the Reallocation Table.

Imagine that in the code we have a variable and a pointer to that variable:

1

2

char Test = 'a';

char* pTest = &Test;

Imagine also that during compile time, the compiler assumes a base address of 0x2000 and the Testvariable will be stored with a RVA of 0x100. Then, the pTest will have a value of 0x2100

However, when someone executes the PE file, instead of being loaded at 0x2000 it gets loaded at 0x3000 . If the pTest keeps pointing at 0x2100 , it will fail. The loader solves this by adding the difference between the assumed base address and the actual one. In this example, the Test variable will be in (0x3000 - 0x2000)+ 0x2100 (the hardcoded address) = 0x3100 .

The .reloc directory contains blocks that correspond to memory pages (typically 4KB in size). Each block starts with a Page RVA, which indicates the base address of the page relative to the program’s assumed base address. Following the Page RVA, each block contains a list of offsets within that page that need to be relocated. The relocation process usually involves adding the difference between the assumed base address and the actual base address to these offsets, ensuring that all addresses point to the correct memory locations when the program is loaded into memory.

Having mentioned all this, we can start talking about reflective DLL injections.

Reflective DLL Injection

The first step in a Reflective DLL is to allocate and write into the target memory address. This can be done by another malicious process (or injector) that the attacker has been able to execute. This process may download the malicious Dll from internet, create it at runtime, etc. the important thing is that it doesn’t need to exist in disk since we won’t be using the LoadLibrary function.

Once the memory has been allocated in the target process, then the malicious process (injector) writes all the content of the PE file (the malicious Dll) in that memory space.

This is not loading the DLL. We are just writing raw data here that Windows doesn’t know how to execute because it hasn’t been loaded.

So, now what?

Remember that PE files have a Export Table with all the exported functions that other processes can use. This table has a specific RVA address. This means that we can get to the beginning of this table by calculating the begging of the allocated space (Virtual Address returned by the VirtualAllocEx function) + the RVA.

So, if we create this ReflectiveLoader inside the Malicious Dll, it will be in the export table, and since we now the RVA of the export table, we are able to know its address inside the process even though the Dll hasn’t been correctly loaded. If we can access the export table and get the address of the ReflectiveLoader function, we can then create a thread that starts at that address so it executes the function.

But Adri, you just mentioned that since the Dll wasn’t loaded properly, it can not be executed. Why would it be possible to execute that function if it is part of the Dll?

That is true and that’s the reason why this function must be “position-independent” since it wont be able to resolve anything in memory (like global variables, imported functions, etc.).

A position-independent function is a function that can be executed correctly regardless of its memory location, achieved through relative addressing instead of absolute addresses.

In a Process Independent function, we can’t declare strings as literals because this will make the compiler to store them in the

.dataor.rdatasection of the PE. Instead, we have to define the strings as a vector of individual chars. This will make them to be stored in the stack, that will be allays accessible thanks to the stack pointer. Hence, instead of usingLoadlibraryAin the code, we have to store this information in a vector like this:

Let’s stop for a moment and analyze what we have explained so far.

- How the injector allocates memory and writes the DLL in the target process

- How the injector finds the

ReflectiveLoaderfunction in the target process memory and creates a thread to execute it.

Ok, so far we just explained what the Injector does. Now it’s time to see what the ReflectiveLoader does. The purpose of this function is to act as the LoadLibraryA function, but it loads itself and since it is a “position-independent” function, it can’t use other functions or libraries to do that, so it has to implement everything itself.

Step 1: Locate the base of the actual Image.

The firs thing that the ReflectiveLoader has to do is locate himself so he can start referencing things. To do this, it will go backwards starting from the return address of the function that called the current function. (This address typically points to the location in memory just after where the current function was invoked):

uiLibraryAddress = caller();

As explained in my other post PE File Structures, all PE’s start with MZ (0x5A4D). So the ReflectiveLoader will go backwards until it finds this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

while( TRUE )

{

if( ((PIMAGE_DOS_HEADER)uiLibraryAddress)->e_magic == IMAGE_DOS_SIGNATURE )

{

uiHeaderValue = ((PIMAGE_DOS_HEADER)uiLibraryAddress)->e_lfanew;

// some x64 dll's can trigger a bogus signature (IMAGE_DOS_SIGNATURE == 'POP r10'),

// we sanity check the e_lfanew with an upper threshold value of 1024 to avoid problems.

if( uiHeaderValue >= sizeof(IMAGE_DOS_HEADER) && uiHeaderValue < 1024 )

{

uiHeaderValue += uiLibraryAddress;

// break if we have found a valid MZ/PE header

if( ((PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS)uiHeaderValue)->Signature == IMAGE_NT_SIGNATURE )

break;

}

}

uiLibraryAddress--;

}

Step 2: Obtain Needed Kernel functions

In order to load everything, the loader needs to use some kernel functions like LoadLibrary , GetProcAddress and VirtualAlloc. This functions are exported by the kernel.dll and ntdll.dll . Luckily, these Dlls are allways loaded in all processes. So, what the ReflectiveLoader does now is:

- Go to the process PEB (Process Environment Block) where there is a list of loaded dll. In this list, it compares the hashes until it finds the ones matches with the kernel and ntdll names.

“A Process Structure is distinct from a PE (Portable Executable) structure. The PE structure defines the layout of an executable file on disk, including how its various sections (code, data, resources, etc.) should be loaded into memory. On the other hand, the Process Structure refers to the data structures used by the operating system to manage a running process, including its memory layout, threads, and resources. When a PE file is executed, its sections are loaded into specific memory regions within the process structure, enabling the OS to manage the process’s execution.

- Once it has located the addresses of the dlls, it searches for their export tables where he will find the VA for the functions needed.

Step 3: Load the image

Now, it is time to load ourselves. In order to do this, the ReflectiveLoader needs to know how big the malicious DLL (ourselves) is. This information is stored in the NT Header of the PE (SizeOfImage).

Once it has this information, it uses the function VirtualAlloc (we obtained its address in the previous step) to allocate enough memory. Then, it copies all the content of the DLL into that memory space.

Step 4: Process the Import Table

Until now we just mentioned the ReflectiveLoader from the malicious Dll file. But this Dll will do “some bad things” and for that it will probably require other functions from other dlls. Hence, these dlls will need to be loaded in the process. This is something that the loader does, so our ReflectiveLoader is also responsible of this task. This is how it is done:

- Load the required modules defined in the Import Table using

LoadLibraryA - After the modules are loaded, it uses

GetProcAddressto obtain the addresses of the required functions. - Updates the Import Address Table (IAT) with the addresses of these functions.

The Import Address Table (IAT) is a runtime data structure in a PE (Portable Executable) file where the addresses of imported functions from DLLs are stored after they have been resolved by the Windows Loader. It allows the executable to call external functions dynamically by referencing their addresses in memory.

Step 5: Process the Reallocation Table

We just explained what is the Reallocation Table in this post and we mentioned that the loader was responsible of computing the difference between the expected base address and the actual one. Hence, our ReflectiveLoader has to do this and go throughout all the elements defined in the Reallocation Table and update the addresses.

Step 6: Flush the Cache and Call the DLL entry point

We are almost done. Before calling and executing the DLL that has been correctly loaded at this point, we must flush the cache NtFlushInstructionCache to avoid using outdated functions after the reallocation has been executed. Finally, we can call the dll entry point (DllMain) and it will do all the bad things he has to do.

All the steps explained previously have been simplified for the sake of the explanation. If you want to read the code that implements all these steps, I recommend referencing this repository of the original ReflectiveLoader, created by Stephen Fewer. But it is a complex low level code that requires a high understanding about C and Windows Operating system.